Key considerations

- Available for £75,000

- 5.7-litre V12, rear-wheel drive

- First front-engined production car to hit 200mph

- Mechanically strong, but 8mpg around town (so avoid towns)

- Often priced on a ‘suck it and see’ basis

- Superamerica hardtop now up to £400k

Thunderous naturally aspirated V12 coupe, anyone? In these electrified days, the idea of a high-character machine like a Gordon Murray T car (for example) can seem like a cold, crisp John Mills-style lager at the end of a prolonged unscheduled stay in the desert.

Trouble is, you’re too late to put your order in for any GMA product other than a T33 Spider, and even that will probably be fully allocated by the time this story goes live. This is all assuming that you’ve got the seven-figure asking price for a GMA car in the first place of course.

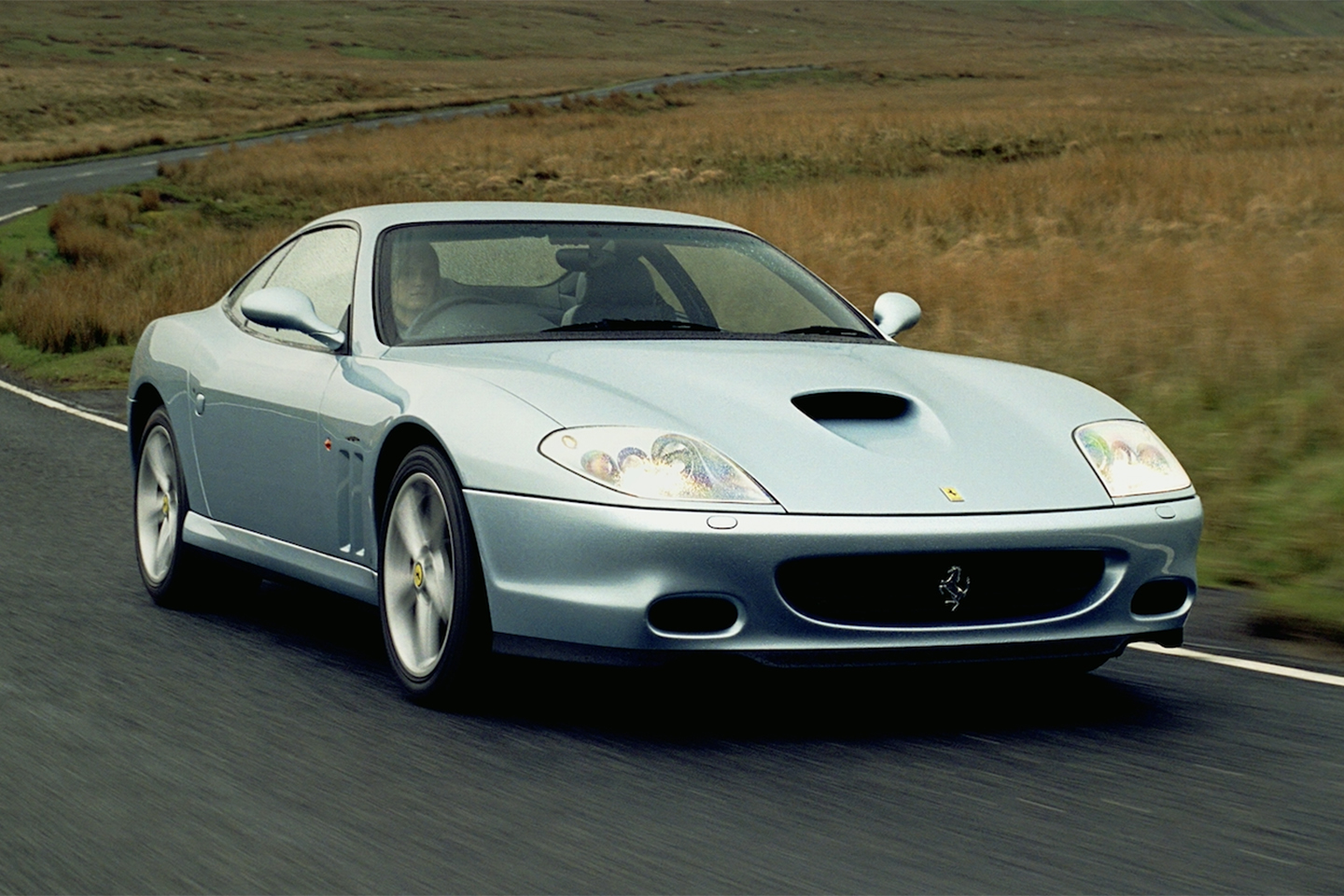

Luckily, nasp V12 naughtiness is available in the classified ads for a fraction of the price of a T33 in the brooding, broad-chested shape of the Pininfarina-designed 575M Maranello that was part of the Ferrari range for just four years in the mid-2000s. Halfway through its production run, one of Britain’s most respected car magazines crowned the 575M as the greatest driver’s car of the previous ten years, praising not only the hugeness of its performance but also its accessibility.

In essence the 575 was an uprated 550, built on the same tubular steel chassis but with a bigger and more powerful engine (575 being shorthand for 5,748cc) and a few other significant modifications signalled by the ‘M’ in the name, which stood for Modificata. On top of its extra power – 515hp versus the 550’s 485hp – it had drilled and ventilated brakes with more servo assistance, different front to back weight distribution, better aerodynamics (mainly achieved by changes to the underbody) and electronically controlled adaptive suspension.

The 575M’s mods added a new level of polish to the 550’s already surprisingly biddable handling, but there was a degree of muttering about it being too soft, so not long after launch the Fiorano Handling Package that had joined the options list towards the end of the 550’s run was also made available for the 575. It consisted of shorter/stiffer springs, a lower ride height, thicker rear anti-roll bar, new suspension electronics, a new steering ECU that reduced assistance at lower speeds, and red brake calipers with uprated pads. The pack was £2,215 in the UK. Not every marque expert nowadays is complimentary about its drive-enhancing value but road testers at the time seemed to like it. Whatever, the FHP’s presence adds value on the used market, although you should be aware that some sellers will claim that a car has the Fiorano pack when it doesn’t. It was an easy claim to make as red brake calipers, the only obvious visual differentiator between FHP and non-FHP cars, could be bought separately.

At the 2004 Paris motor show Ferrari announced a Handling Gran Turismo Competizione pack (HGTC) for the 575M which moved chassis matters on to a new level. We’ll talk more about that in the conveniently titled Chassis section.

As with the 550, the 575 had two driving modes, Sport and Normal, but for the 575 there was now a choice of two rear-mounted 6-speed gearboxes, either the 550’s classic ‘clackety-clack’ manual or, making its debut in a Ferrari V12, the ‘F1’ automated manual supplied by Graziano Transmissioni.

For 2005, a year before the 575 run ended, Ferrari released a Superamerica drop-top. Like the coupe, it was available as either a manual or an auto. The Superamerica name harked back to a couple of powered-up American-market road cars from 1956 and 1960, and the 575 version followed that tradition. Its mainly red engine with grey manifold and valve covers was uprated from 515hp to 550hp to offset the extra 60kg that had been added by the unique electrochromic glass and carbon fibre ‘Revochromic’ electronic hardtop. This pivoted 180 degrees from a point behind the driver’s head to finish up flush on the boot, where it became a wind deflector. It was an elegant and simple design. Unfortunately, for many owners it turned out to be a point of frustration. We’ll get into that later. With the roof safely up the Superamerica was the world’s fastest convertible at 199mph.

The 575M lasted for just four years in the Ferrari range. In 2006 it was replaced by the 620hp 599 GTB. 2,056 575Ms had been built. Early, higher-mileage UK examples of the 599 start from about £80,000 but the older 575M has accumulated enough fans for its entry price to be pegged at a very similar level. We have seen UK cars for sale at £75k, so we’re quoting that as the minimum price point in the spec panel below, but £80k is a more realistic jumping-off point. Five years ago (in 2018) we would have been giving you almost exactly the same figure for used 575s.

Left-hand drive 575Ms are sometimes cheaper in the UK, spec for spec, but there again overseas buyers will happily pounce on a UK-based car and ship it home – particularly as it’s easier to trace a car’s history over here thanks to HPI and the like – so the price gap won’t necessarily be as wide as you might expect. It goes without saying that your scrutiny of a car’s paperwork should be as forensic as possible.

559 Superamericas were built, 62 of them supplied to the UK where the manual version cost £191,000 and the F1 £198,800. Quite a premium on the £154,000 coupe, but as we’ll see at the end of this story the cheapest secondhand Superamerica you’ll find for sale at the moment is priced at the same sort of money as when it was new, and low mileage examples are more than double that.

SPECIFICATION | FERRARI 575 M (2002-06)

Engine: 5,748cc V12

Transmission: 6-speed manual or automated manual, rear-wheel drive

Power (hp): 515@7,250rpm

Torque (lb ft): 434@5,250rpm

0-60mph: 4.2 seconds

Top speed: 202mph

Weight (kg): 1,690

MPG (official combined): 12.9

CO2 (g/km): 499

Wheels (in): 8.5×18 (f), 10.5×18 (r)

Tyres: 255/40 (f), 295/35 (r)

On sale: 2002 – 2006

Price new: £154,350

Price now: from £75,000

Note for reference: car weight and power data are hard to pin down with absolute certainty. For consistency, we use the same source for all our guides. We hope the data we use is right more often than it’s wrong. Our advice is to treat it as relative rather than definitive.

ENGINE & GEARBOX

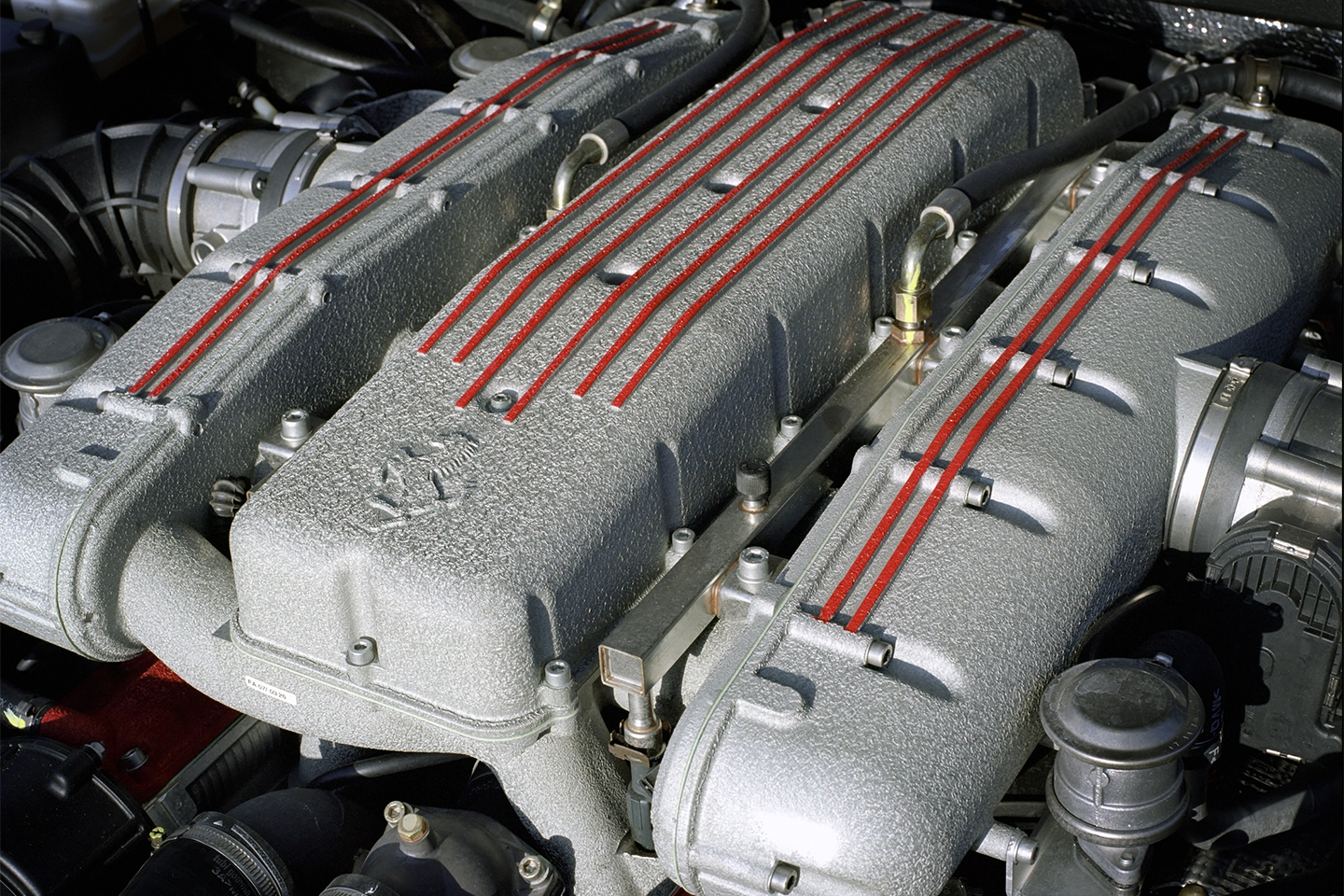

Considering its large displacement, the mighty F133 5.7-litre V12 revved for fun. Its liveliness was thanks in part to the lightweight spec of its reciprocating parts, which included titanium conrods and forged Mahle pistons. Naturally, an engine that size was always going to have lots of torque as well as high-end fizz, so you could enjoy it equally in mad or mooch mode. 1,690kg seemed like a lot in 2002 when the 575M was launched, but our attitudes are very different now with 2,000kg seemingly the new norm for luxury and performance cars and even 2,500kg hardly raising a comment. Either way, 1.7 tonnes didn’t stop the 575 roaring through the 0-60mph in the low four-second bracket and storming on from there to 200mph.

If you’re thinking of taking the plunge on a car with a non-standard exhaust, drive it first to make sure that you can put up with the noise, as not all of these pipes delivered a sound that you could tolerate on a long trip. A big part of the 575’s appeal lay in its cruise-ability and you wouldn’t want to kill that.

Eight out of every ten 575s were ordered with the single-clutch F1 automated manual gearbox, with only 246 ‘real’ manuals produced in total. For the Superamerica the ratio of autos to manuals was more than nine in ten. This gives you an interesting snapshot as to what was considered desirable back then.

Of the 251 right-hand drive 575s built for the global market, the vast majority of those being for the UK, 69 had a manual gearbox. When you see that only 246 manual 575s were made altogether, it’s clear that the British taste back then was very much for three-pedal Ferraris. Today, there’s a hefty premium to be paid for the manual box on like-for-like 575s, suggesting that the Brits were right from an investment perspective at least, but some say that that the auto/manual price differential will narrow over time as younger buyers who are more accustomed to two-pedal driving come through with sufficient readies.

The six-speed manual does have a decent reputation for longevity and reliability, and its action was somewhat improved from the old 550 days when baulking into gears (especially the odd-numbered ones) was par for the course. However, the clutch and its release bearings can still get grumpy over time, particularly if they’re not being used that often.

The F1 box didn’t work that well in some applications (for example the Maserati GranSport) but it was actually a decent fit with the digitally-throttled 575M and it was certainly superior to the contemporary Aston Vanquish’s similar transmission. When the F1 was in its manual setting the 575M driver could switch from Normal to Sport to access faster times and firmer suspension. Ferrari reckoned that the auto was marginally faster through 0-60mph than the manual.

It’s far from unusual to see notes of major transmission work on the service histories of higher mileage F1 575s. Sensible owners faced with the prospect of gearbox-out work didn’t need much persuading to have other precautionary work carried out at the same time, for example installing new clutch and sensor assemblies and maybe a new rear main oil seal. That’s the good part about buying used Ferraris. Most (but not all) previous owners will invest whatever money and time is needed, and then some on top, to protect their investment by maintaining the integrity of the service history.

What might that money be spent on? The engine itself is very robust but you might experience misfiring which could be down to dying HT leads. Premature wear to the engine mounts on the old 550 led Ferrari to beef them up for the 575 but they can still wear. Vibrations at idle are a sign that things aren’t right in that department.

Coolant radiators could start to weep either through corrosion or because of cracking caused by temperature extremes. These can be refurbished. The coolant hoses that live in the vee of the engine were also under a lot of heat stress, leading to a predictable outcome. Buying a set of stronger silicone hoses won’t be that ruinous, but the labour involved in fitting them after removing the old ones will bump up the bill considerably.

Whirring from the front of the crankcase was a sign of worn bearings between the crank pulley and the timing gears, a £1,000 job including cambelts. These belts needed to be replaced every five years irrespective of how few miles the car had done, otherwise you ran the risk of damage through disuse. The bearing for the belt tensioner could seize up in such circumstances. Leaky camshaft oil seals might also hasten a cambelt’s demise.

Servicing? Even a basic whizz-through is going to cost you the thick end of £1,000 at a main dealer. Official warranty extension packages like Power15 don’t cover the 575M or Superamerica, and even the Ferrari Premium plan only just covers some of them as it’s only for cars up to 20 years old. After that, you’re into the Ferrari Classiche programme, and that’s not cheap. Precise pricing information on these programmes, or on main dealer servicing, is not publicised.

Independents like Simon Furlonger in Kent do publish prices online. They offer fixed-price servicing at £895 for the annual, £1,450 for the major including spark plugs, and £2,195 for a cambelt change plus service. One Ferrari Owners Club member said he did most of the basic servicing himself, reporting costs of around £200 a year for oil and filter changes and the occasional brake part. His car would go in every three years for a proper service and software updates, for which he budgeted £1,000. He said that a blown fuse was his only unexpected expense in 30,000 happy miles. The official fuel consumption was 12.9mpg combined and a magnificent 8.2mpg urban but you don’t care about that.

CHASSIS

In the overview we mentioned the Fiorano Handling Package that was seen as slightly unnecessary on the 550 but a worthwhile option on the early 575s, which some considered to be too soft. The Handling GTC pack announced in late 2004 could be categorised as a maxed-out FHP. HGTC springs were 35 per cent stiffer at the front and 15 per cent stiffer at the rear, working with revised dampers and a 73 per cent stiffer anti-roll bar. On the Superamerica the HGTC pack included the fitment of Bridgestone Potenza RE050A tyres instead of the usual P Zero Corsas.

The HGTC price was maxed out, too, at over £15,000. At least half of that was swallowed up by the 398mm/360mm carbon ceramic brakes with six-pot calipers at the front. It was the first appearance of carbon brakes on a front-engined Ferrari. Replacing the standard 330mm/310mm iron discs and sitting in new five-spoke 19in split rims with 255/35 and 305/30 Pirelli P Zero Corsa tyres, the carbon brakes trimmed a reported 10kg per corner off unsprung weight.

You also got a lighter, noisier, but no more powerful exhaust system, some remapping of the F1’s auto transmission, a new ‘egg-crate’ aluminium grille and carbon bits in the cabin. Fitting the HGTC resulted in a big improvement in body control and a claimed 1.5sec lap time cut on Ferrari’s test track. All that weight up front didn’t give the tyres, suspension or steering an easy time. Tyres would typically wear on the inside edges where you might not always spot it. Driving a 575M hard should give you around 10,000 miles a set. Double that mileage for gentler use.

Suspension bushes get tired, particularly those on the upper wishbones, and particularly if power steering fluid has been dripping on them, which can happen. Clonking over bumps is the giveaway there. If a car seems a bit low on one corner it’s probably because the spring has broken. Leaks can affect the dampers, but these can usually be refurbished. To help avert suspension problems it’s worth regularly changing the driving mode rather than just leaving it in the same mode all the time.

It shouldn’t be necessary to spend a lot of money on chassis hardware to improve the 575. It already had a limited-slip differential and excellent quality suspension components. The best way to optimise the drive was to keep the car properly maintained and well set up on its standard geometry.

BODYWORK

Some of the 575M modification work was to the front-end styling, centring mainly around a reshaped bonnet intake and spoiler and new xenon headlights, plus very minimal tweaks to ease air flow past the wheels. Not everyone thought these changes represented visual improvements over the 550. Scuderia Ferrari shields were an option for the front wings.

Rust is rarely seen on 575M bodies as they’re mostly aluminium and well protected, first by the factory and then by the owners. Even so, if you’re thinking of buying one it would be bonkers not to have an expert do a thorough examination, including critical parts of the car’s bodywork that you wouldn’t normally see like the wing inners. Experts would also be able to pick up on any odd panel fits, suggesting an accident. Crash damage wasn’t something you could protect yourself from, other than by storing the car and never driving it, and of course many owners have done just that, especially the Superamericas. We’ll link you to some of those in the Verdict section.

Colour is always important on any Ferrari, from a resale perspective if nothing else, and that applies to the 575M. You’ll have no trouble finding cars in various shades of grey, and if you want to save money and operate below the radar these less vibrant hues can be a sensible choice. They’ll often be cheaper than strong primaries like blue or red but of course you won’t get so much back when you sell them on.

Ferrari patented the Revochromic pivoting hardtop on the Superamerica. You can see why. It was wonderfully simple, there was no intrusion on boot space, the deployment process took less than ten seconds, and as a bonus you could adjust the degree of glass tint via a console knob, although that was a somewhat slower process than roof deployment. It took a full minute for the glass to switch between the two tint extremes.

Unfortunately that Revochromic patent wasn’t put to the test by rivals who may have been contemplating something similar because just about every Superamerica had significant problems with its roof. The carrier mechanism had to be made small to fit into the area allowed for it and it wasn’t man enough to stand the strain of continually hoisting the heavy glass. The gas struts failed, the glass delaminated or cracked, switches blew and the ECU got mixed up. Some found that the roof worked more reliably when the engine was off, relying entirely on the aux electrics. Factory fixes were developed, but it was a pity that that development didn’t happen before the cars went on sale. The boot lid on the Superamerica was made of carbon fibre, incidentally.

If you spend a lot of 575 time at three-figure speeds you should keep an eye on the integrity of the undertray fastenings, as wind pressure will seek out any weakness there and drag the trays away from the main body. These are old cars now, so anything that needs to be flexible like door and window seals needs to kept fresh.

INTERIOR

Pininfarina was given the green light to more or less completely re-do the interior on the 575M. The dash, instrument and centre consoles, steering wheel and door panels were all new, with the electric window switches being moved from the top of the grab handles to the front of the armrests and a digital fuel gauge added for a spot of modernity. The six-way adjustable electric seats with optional contrast seat piping and inserts were a new design but Daytona seats were, as ever, a desirable option.

Satellite navigation was optional, as were typical Ferrari grand touring extras like fitted luggage, a ribbed or quilted parcel shelf and carbonfibre trim pieces for the dash, centre console, doors, steering wheel, gear lever, door sill panels, handbrake housing and seat guard covers.

Shrinkage of the leather around the 575M dash and instrument binnacle (caused by dodgy glue) is quite common. Ask your Ferrari dealer to rectify that with the correct hides you’ll be presented with a bill for something in the order of £5,000. It was easy to cause damage to the leather around the hole for the Becker radio if it was replaced with something jazzier. Control knobs got ‘sticky’.

PH VERDICT

From a cosmetic and driver engagement perspective, the 575M was perhaps not as universally loved as the 550. Those elements are very much in the eye, or seat, of the beholder, but there was no denying the bombastic road-swallowing potency of the 575’s performance. It was the first front-engined production car that could top 200mph, a hell of a feat in 2002 and still impressive today.

Although we can identify £80k as a typical starting point for right-hand drive cars it’s not so easy to get a handle on 575M prices above that. Owners who are in no hurry to sell will often put crazy prices on their cars and then sit back to see what happens. Mileage, colour, history and the side the steering wheel is on will all affect values but not to the same extent that have-a-go pricing will. It’s not unusual to see £100k difference between two cars that to all intents and purposes are nearly identical.

To illustrate that, let’s look at two Superamericas on PH Classifieds. The initial problems with the Superamerica’s roof were sorted out and their rarity has made them more of an investor’s than a driver’s car. This collectability is reflected in the prices. Here’s the most affordable Superamerica on PH, a 20,000-mile automatic from 2006 at £1 under £190k. Here’s another one registered in 2007 and with 13,000 fewer miles. Obviously, you’d need to do some digging to work out why the second one is nearly £90,000 more expensive than the ’06 car, or to put it another way, why the ’06 is £90k cheaper. There might be perfectly good reasons for the disparity. There again, you could just say ‘hang everything’ and blow £400k on this as-new specimen with the HGTC chassis package. It’s only done 300 miles but the single owner has put 12 main dealer stamps in the service book.

Back in what passes for a more normal 575 world the top end of the market is populated by ‘POA’ cars. There were three such 575s on PH Classifieds at the time of publishing, one a grey ’04 manual, one a black ’03 with 3,600 miles and the other a grey ’03 with 28,000 miles. Who knows how much ‘POA’ means in this context but the most expensive 575 with a price tag on it was this Dutch manual at 279,500 euros, or just over £247,000. And that car has 83,000km on it.

This was the most affordable 575M on PH Classifieds at the time of writing, an ’03 auto in Rosso Corsa with black leather Daytona seats and 21,000 miles recorded. It’s a left-hand drive car and we’re not told how many owners it’s had, but the vendor does say that there is a full service history. If nothing untoward shows up in your research it might well tempt you at £77,000. PH had a good selection of autos for under £90k as we went to press but there were no manual cars below £159,950. This one has 33,000 miles. Or, to save yourself £40, buy this one.

#Ferrari #575M #Buying #Guide